Over the dozen mobile missions I worked on, the main caveats of codebases I faced were that the Model is unclear and disseminated, and data paths and behaviors are hardly readable.

This article digs into these problems and offers concrete directions on the architectural level, as well as some advices on the implementation level.

It’s not supposed to create a new shiny big-brained architecture abstraction, but it rather aims to explicit practical design advices that should bring clarity and reliability to your app’s business.

This article’s scope is wide but I tried to make it concise enough. It’s addressed to developers and architects of intermediary to expert level. It’s also deeply anchored in my own experience, including all the biases it can carry.

TL;DR

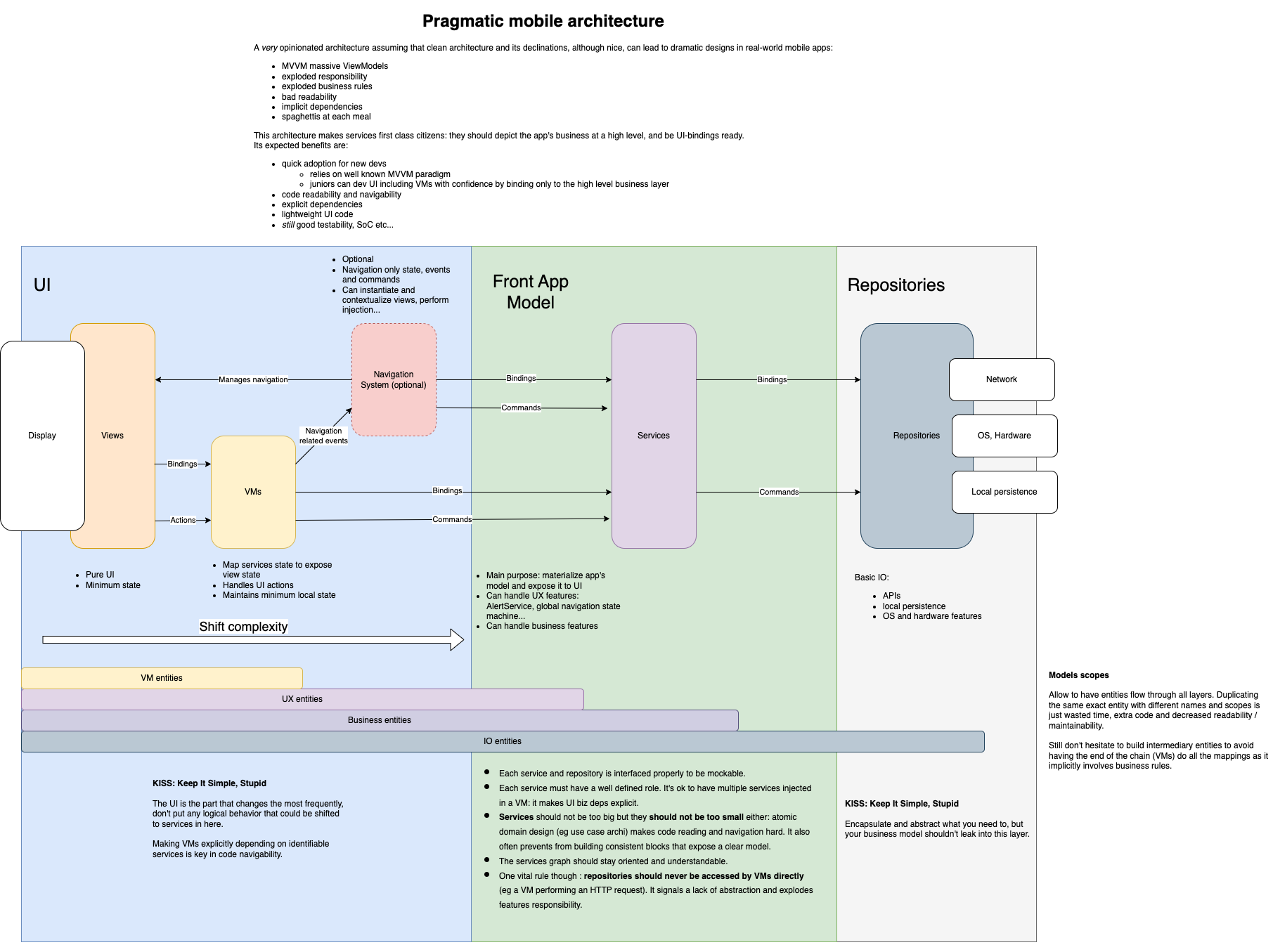

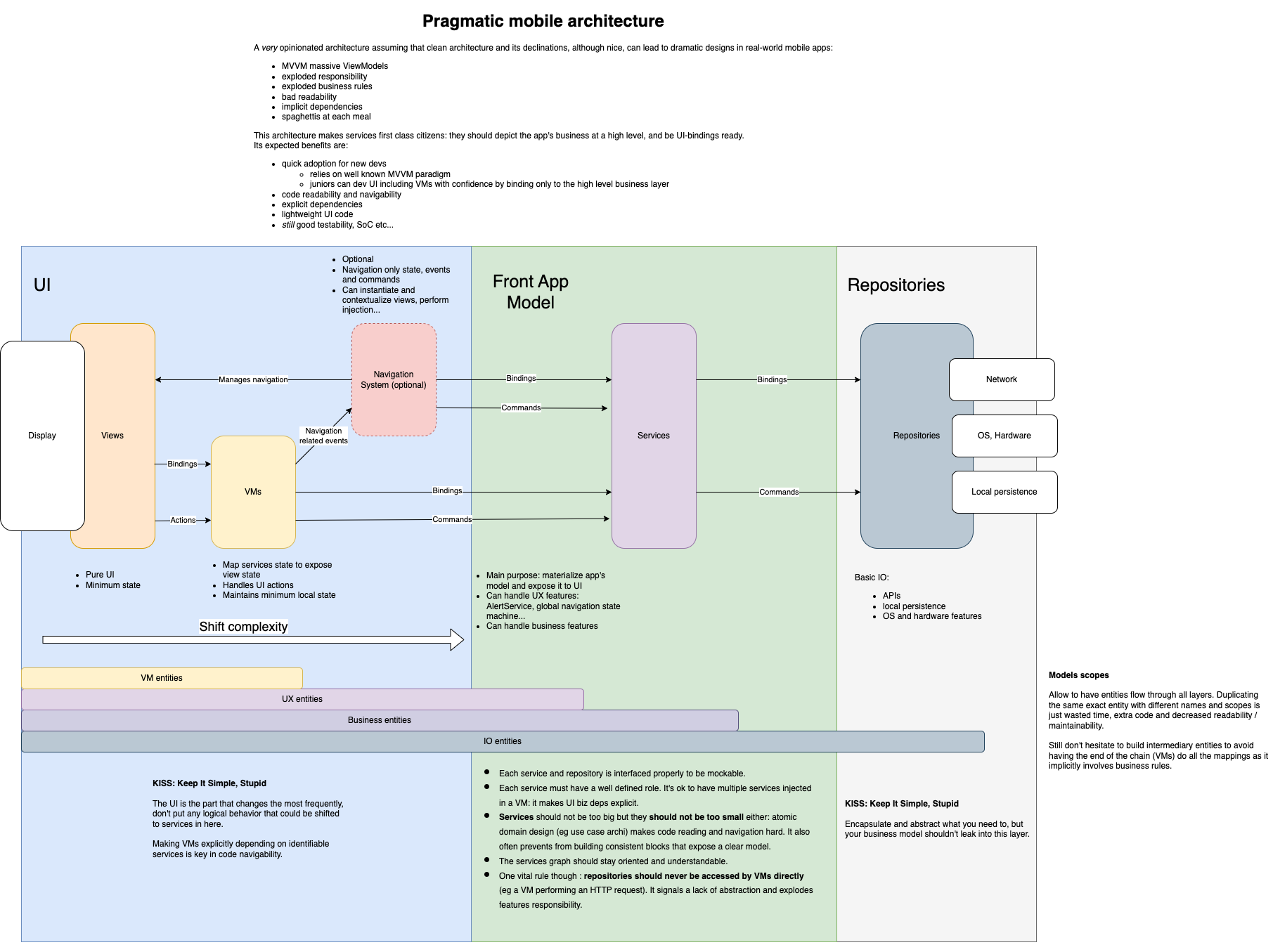

⚠️ The diagram below can look like a new annoying architecture claiming to be the state of the art.

Well it’s not.

Further you’ll see multiple mitigations, for example about the need of some Repositories. Also, I do not introduce new layers or too strict data paths (like VIPER does) that lock you in a specific paradigm.

This article is about practice and pragmatism, and the balance to avoid both spaghetti code and over-engineering.

Still, this is a “TL;DR” so here you go!

I. Model and Repositories concepts in architecture patterns

Mobile devs often mistake Model for “data model”.

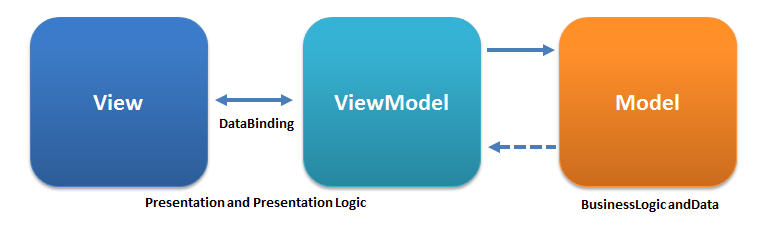

Here is the Wikipedia’s schematic of MVVM:

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Model–view–viewmodel

Well, “Business Logic and Data” seems to be much more than “data model”.

When you’re searching about mobiles architectures online, it’s in fact one of the most precise descriptions of the Model you can get.

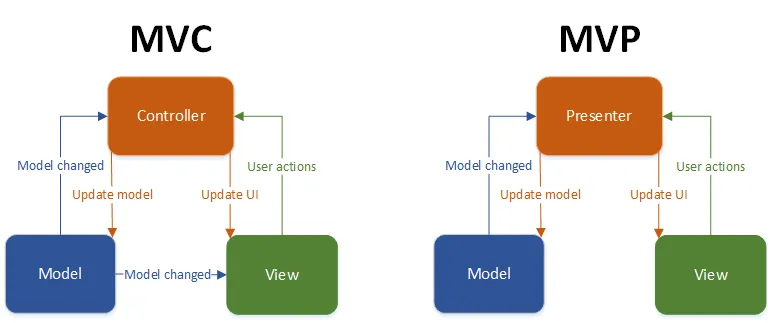

From https://www.techyourchance.com/mvc-android-1/

Sometimes, the Model is just assimilated to Repositories.

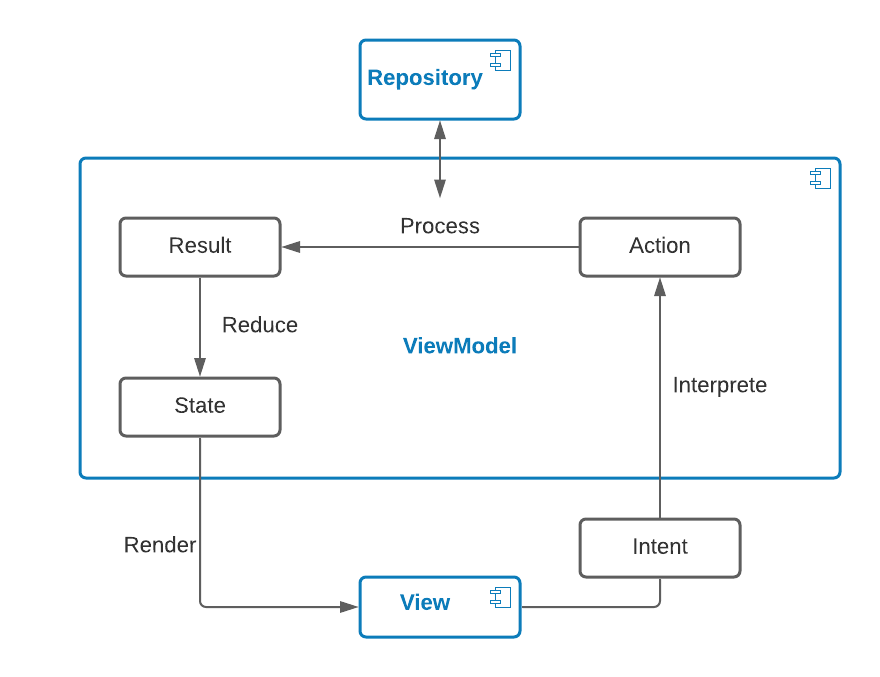

From https://medium.com/swlh/mvi-architecture-with-android-fcde123e3c4a

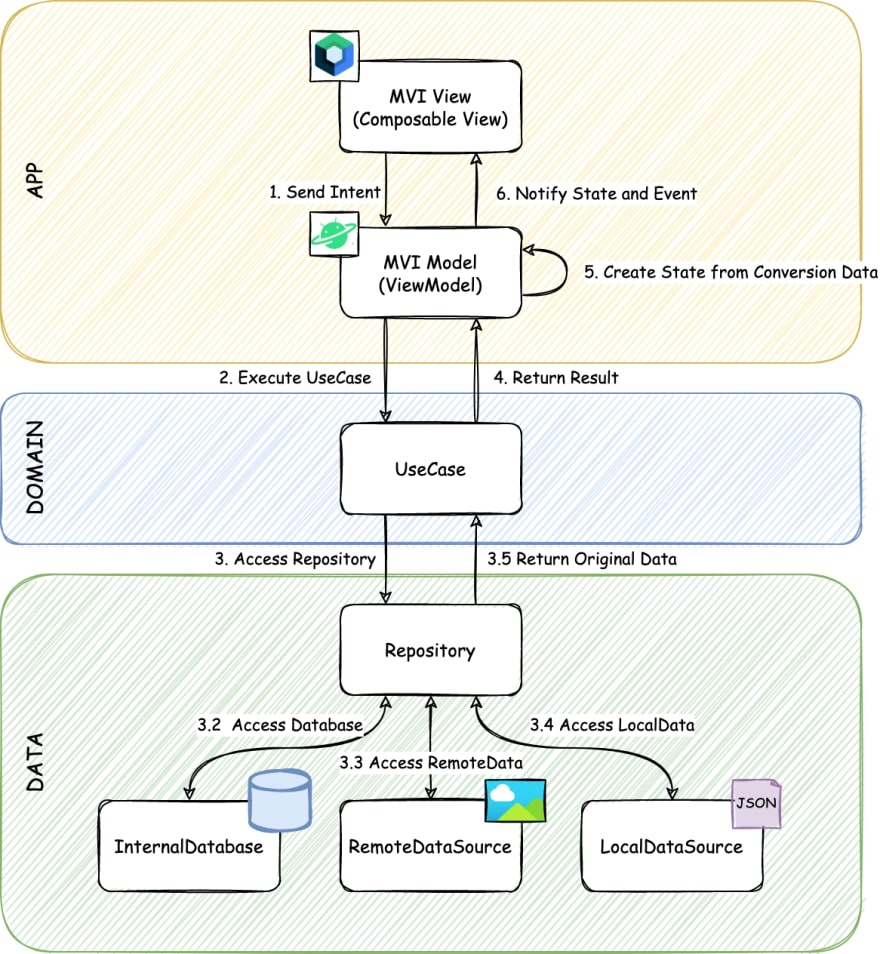

And sometimes there’s something between the ViewModel and the Repositories.

Namely UseCases:

From https://dev.to/kaleidot725/implementaing-jetpack-compose-orbit-mvi-3gea

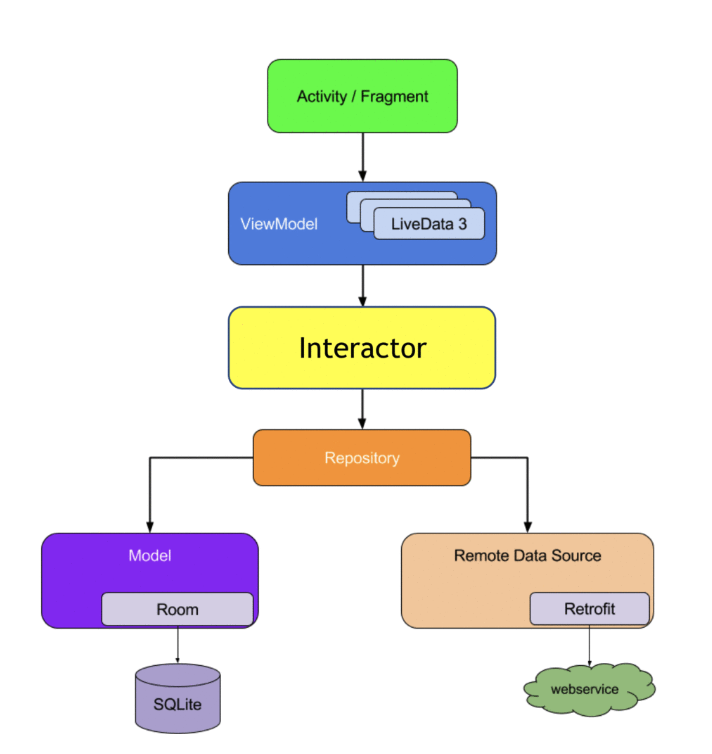

Or Interactors:

Of course you can find infinite minor variations of such schematics, with local models for example like above, or ViewModel’s model.

But in most cases the terminology is:

Model: Business Logic and Data

Repository: API with a backend, a local storage, a SDK…

II. The Problem

MVC, MVP, MVI, MVVM… There are many paradigms helping you bind your business logic to your actual UI implementation. But in the end, none of them is meant to help your with your actual business logic implementation. Well there’s VIPER and friends, but I’m trying to avoid over-engineering here.

The first step in dealing with this issue is usually to identify the model to the repositories. What you get when your apps starts growing, is often ViewModels reuse: ViewModels are not always tight to one specific View because you need some business logic that it implements in some other part of your app. And then you start carrying extra business logic to many Views because you needed a piece of it, and your architecture becomes fuzzy.

The second step is to look at clean architecture principles and its applications in the mobile context, and introduce UseCases or Interactors (couldn’t get the difference in implementations I actually saw). And in fact, that’s a nice step: now you’ve got identified entities that carry your business logic.

The third step is to get overwhelmed with instabilities or maintainability problems even though you were very thorough in your intermediary layer implementation.

The final step is to switch to a new project, hoping your problems were intrinsic to some other part of the app - typically the backend - and you may not find them in this whole new shiny project.

III. The solution: materialize the Model

First things first: you need that extra layer between your UI (Views and ViewModels) and the Repositories. If I were to define terms again, I would call this the Model. And I do in the scope of this article.

UI should be dumb as hell. It changes often, and you don’t want to embed any business logic in it.

Repositories should be dumb as well. They are only interfaces to CRUD systems, SDKs or a backend, all the related complex work is done inside them.

Shift all complexity you can to this business layer. And organize it.

Isn’t that what UseCases and Interactors are supposed to do? Well it really depends how you implement them. The usual caveat is that these terms imply unitary implementations: each one is focused on one specific task (getting some data or executing a command).

You just atomized your Model.

Reusing common code inside a feature brings more files and code navigation becomes harder and harder. Some build a graph of UseCases and in the end, the issue is that it’s just not readable. New needs will be implemented poorly if done by a dev that doesn’t know the graph on its fingertips.

So let’s call the entities of this business layer something else. Arbitrarily I’ll call them ✨Services✨, but feel free to choose your own terminology. And let’s make these Services more consistent.

IV. Model’s theory

From my experience, apps that have the least bugs have a Model that is:

- compact

- thorough

- split in enough and not too many Services

- actually depicting the app’s domain

And one of the best way to achieve that is to conceive it.

Take your hands off the code and draw your Model.

I must insist because too many devs are focusing on UI first, then try to bind it to the repositories while considering that 99% of the work already done, and don’t bring enough care to this step.

In fact, my favorite approach is to conceive and implement the Model first, before even writing the first line of UI code.

A good model implements the app’s domain while accounting for practical constraints.

1. App’s domain representation

a. Your Model has Entities

Not only backend’s one (and often not all of them): your mobile app is not just an externality, it has its own business to mind!

b. Services contracts should be exposed

The inputs (commands) and outputs (values, events) of each feature (the Service’s responsibility) should be gathered and have a place to stand.

c. But what IS the app’s domain?

It’s how you represent the world knowing:

- what interface you need to provide to the UI for it to perform its job

- how the Repositories behave

- and what actual work should be achieved in between.

It’s not what the repositories do or what the UI does, but it’s the abstraction of what the “bindings” manipulate and do.

2. Practical constraints

Our domain describes the business that happens between the UI and the Repositories. As such, it must account for input and output abilities and needs on both sides.

To put it another way: as the app’s domain stands for the Model’s design, the constraints of the Model’s I/Os should be considered in the domain.

Concretely, what can these constraints be then?

a. The UI navigation

The Model should not take care of the navigation, but it should definitely drive most of it in the sense that UI components (like VMs, or Coordinators for UIKit veterans) should be able to perform very direct navigation flows while staying dumb enough.

b. The UI SDK

There aren’t many alternatives in the mobile world anyway, but mainly if your UI SDK is declarative or imperative (SwiftUI vs UIKit, Jetpack Compose vs legacy Jetpack) can make a great difference.

c. The UI architecture

Should you decide to use MVVM, MVI or TCA, all of them don’t define your model. But they might shape your model output: Do you better store a global reactive state or divide it by feature, by flow?

d. The repositories natures

A RESTFul API, a reactive NoSQL storage (like Firestore), a local relational DB with an ORM, an IoT SDK… Each kind of repository has specific constraints: it may be asynchronous or not, online or not, and expose specific paradigms that may impact greatly how the entire app should work.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t abstract many specificities of the repositories, but that some of them sometimes shape at least a bit their abstraction anyway.

3. What your Model feels like

I think that there are three great criteria to judge if your Model is well written.

- If you take a look at your Services interfaces / protocols and your entities, you should see a satisfying representation of your domain. Don’t think about the implementation, don’t think about UI details: do you see your domain while reading your Model?

- If you think about binding your Model to the UI you’re supposed to build, are the bindings obvious?

- If you think about using your Repositories to create these Services, does it make sense?

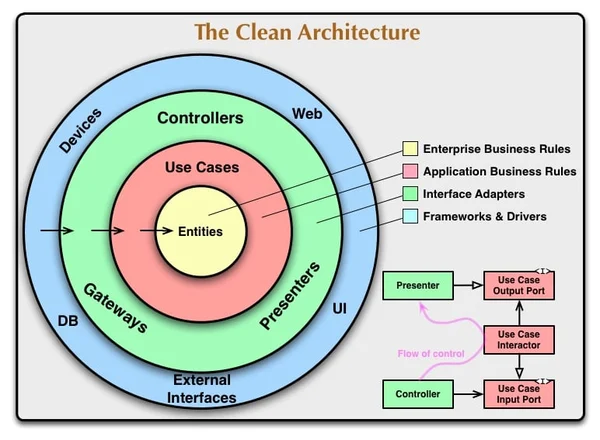

V. Quick parenthesis: Clean Architecture

In Android especially (I guess because it’s a child of Java culture), there is a great influence of Clean Architecture theory. Sometimes, layers separation concerns come at the point that you may have the same entity duplicated 3 times for theoretical reasons, but bringing literally nothing in practice - worse, sometimes introducing weaknesses. That’s just not pragmatic and I would advise you against these kinds of maniac satisfaction.

There can be good reasons to follow unproductive rules, and the limit is thin between good design principles and a blind worship.

So a couple of advices you can go with is to read a lot about clean architecture (it’s a very nice theoretical basis) and to adapt theory to what actually works, in practice and for your team.

My proposal should mostly fit in Clean Architecture paradigm, but I don’t consider it necessary.

About that, let’s take a step backward.

VI. Pragmatic Mobile Architecture

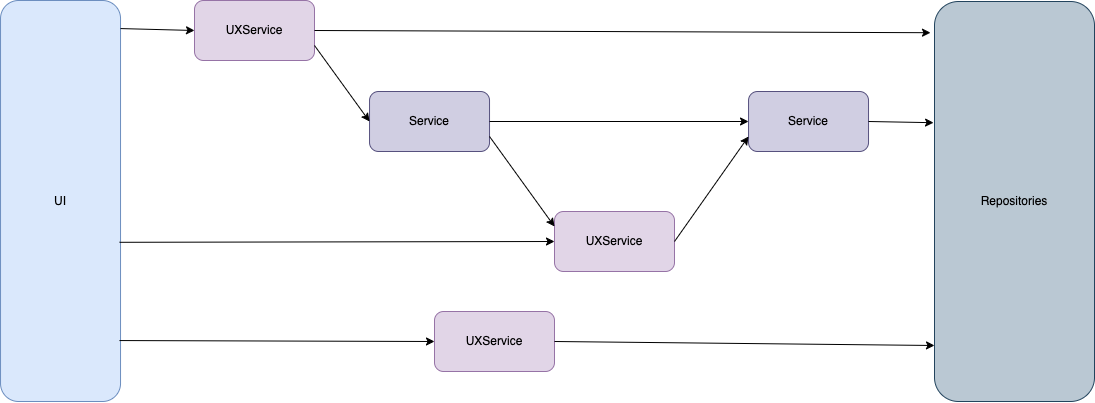

I drawn a concise representation of the architecture I use in all my mobile jobs and missions. Don’t ignore the text in it, it’s not decorative but really part of the architecture. Else it’s just totally similar to UseCase/Interactor architectures (except for the naming).

First, you will find that this architecture is compatible with MVVM, MVI, MVP… Of course, as I focus on the (green) Model part, you can tune the details of the UI layer as you wish.

Then you can see that my graph is kinda oriented (well navigation is a strange beast), and that’s a quality that I kept from Clean Architecture. It’s really a key point to make things clean.

Another point hidden in the text, is that Services form an oriented graph. To explicit things a bit, it means that this Services graph:

.png)

is totally valid. I know it can be tempting to have explicit Service layers and to apply isolation rules between them, but in practice I’m convinced it’s terribly counter-productive. I’d say we’re stepping in the overengineering area.

Note that an obvious golden rule is to never-ever let UI use Repositories directly. If you do so, you’re missing modeling. Also, even if it can be a local reasonable shortcut, it will make precedence and you’ll soon be back in the spaghetti hell we’re trying to escape from.

On the opposite, sometimes it does not make sense to create some Repositories.

I also just materialized what I wrote earlier about entities: I happily let them flow from Repositories to UI when it’s relevant.

Finally, what’s not described in this diagram is how to design your Services.

VII. Service design and beyond

I gave you a few directions on what the app’s domain and its Model are. This should lead the theoretical conception of your Services. Then I briefly presented my favorite shape of Model architecture. Now I want to share how I actually implement all of this with a simple list of practices. It’ll be a lot less structured, more opinionated, but you can see that as pointillism. Crossing all of these should define a relevant frame to write a good Model with nice intrinsic qualities, and still with a good performance.

1. CQRS everywhere

CQRS stands for Command and Query Responsibility Segregation.

In our context, it translates to:

A function can either query data or execute a command, but never both.

It can seem dumb and/or impractical, but just applying this rule will enhance your data flow and your commands flow readability more than you’d expect.

I admit, there are high value exceptions sometimes, beginning with the result of a command (that is actually data). But in many cases, the data that a command would return is either:

- a success / error flag that can be ignored by the caller and taken into account by the Service, making potentially this event flow in a query channel if needed

- updated data that is already bound via a query channel

A specific mention here for reactive programming: it’s even more important in this paradigm to avoid side effects and not mix query streams and command streams (as it’s easier to confuse them).

2. Reactive, async, imperative…

My personal balancing lead me to use reactive programming in a very limited scope. The main reason for that (putting aside my personal taste) is that most devs are used to imperative programming, and reactive programming adds a big overhead to their project onboarding. Readability for junior devs and staffing ease are actual concerns. It also brings intrinsic qualities to your Model.

Thus I advise to use reactive programming:

- only for queries relative to reactive data exposed by services. By reactive data, I’m speaking about values that can change over time. A counter-example is an HTTP request as it encapsulates an execution returning a single result: an asynchronous function will be way more explicit for this purpose. On the contrary, a service exposing data that may be fetched or not, or updated at any point should expose a reactive stream.

- by using streams that always provide a value as soon as you subscribe to them, except for events of course. Use nullables, enums with associated values (Swift) or sealed class (Kotlin) to represent initial values if needed.

- by publishing only values and make your streams error proof. Manage errors ASAP, and turn them to Model states or values (or ignore them if it’s relevant), before even emitting through reactive streams:

- it’s simpler for consumers, there’s only one linear stream to handle. Else many will just consider them as an unwanted consequence of Services business implementation and in many case wrongfully ignore them.

- it forces you to make errors management explicit and in the right place. One Service’s model can be designed to expose its errors explicitly, and another one’s consuming it can handle their side effects and expose an errorless Model to UI.

- by not exposing completing streams. Handling the end of a stream is another difficulty that should be handled ASAP, for the same reasons as errors. It makes a lot of sense if you use reactive streams only for reactive data queries (first point). So

flatMapinternally as much as needed, or use relays that won’t complete, and if you still want to let a stream complete (it can make sense), just don’t expect consumers to handle it. - still allowing direct values exposure when it’s needed from consumers. A plain old var is straightforward and explicit, and sometimes a one time value is needed. Don’t make things complicated for consumers when they should be exposed simply.

This way, most of the unknowns and difficulties of reactive paradigm go away.

Note that we can do this because Swift Concurrency and Kotlin Coroutines have made their holes.

The reactive hell trying to fix the callback hell is no longer a thing: what is asynchronous should be asynchronous (using either async functions in Swift or suspend ones in Kotlin).

Still, I suggest to make asynchronous functions private in most cases. If the result of an asynchronous command is not needed or can flow through a query channel without adding complexity, the consumers will bless you. Also, checking which function is called in an asynchronous context will be much easier.

But of course, if your ViewModel needs to perform a single remote command and it’s relevant that it’s it that locally manages the loading state of its View, then don’t overthink and make your asynchronous function public.

3. Main Thread is the place to be

In mobile apps, you know that when any event or data triggers the UI, it should happen on the main thread. So let’s try to do everything here!

If there’s a sensible performance issue, identify what should be done in the background and encapsulate with clear boundaries what code will run in the background. But don’t do it by default. If you’ve got 1000+ entities to process and map, don’t be frightened by big numbers and just check the execution time if you have any doubt.

Sometimes, your performance issue is caused only by bad code. Manually finding relationships between huge lists of entities with nested loops can be unnecessarily long to execute: optimize it and use caches, Sets or HashMaps (Dict for Swifters) instead of moving your process to the background in the first place.

If you still implement a background task and it should trigger anything else (publish on a reactive stream for example at any point of some heavy process), do it on the main thread.

Some would rather try to always make ViewModels consume what Services provide on the main thread. But it’s not enough. Not knowing by default if any Service output will happen on the main or a background thread is too risky. It can also lead to concurrency issues and unexpected race conditions in the business code. Monothread paradigm is simple, comfortable and safe.

4. Avoid inheritance

OOP is no more the center of the world, and its nice principles are no more the state of art. The issue with inheritance is that it’s a bit hard to design properly, implement and read, especially for juniors. In simple case it’s not of course. But in general it can easily be split down to interfaces (protocols), composition, value types and concrete utilities. Your Model’s quality will increase while doing so.

As usual, stay pragmatic. If you see a real benefit to inheritance and the alternatives are overkill, then use inheritance.

5. Do you really need this Repository?

Don’t be systematic in your architectural approach on this point. A great example is user preferences (UserDefaults in iOS, SharedPreferences in Android).

If you have a simple utility function that takes a key and allows to build a get / set / reactive-stream property from it, using it inside your Service directly is way simpler than grouping unrelated explicit properties in some store.

In this case, ideally, don’t write a store interface and implementation.

Sometimes the store is needed. Well in that case, make it expose generic accesses and declare your actual properties in your Service. After all, each preference property is part of your domain and the best place to expose it is inside the Service responsible for its feature.

Opportunistic ad: for iOS I engage you to try my neat reactive PDefaults property wrapper 😁

A rightful objection: “Isn’t it the same for APIs? Why should I expose all endpoints in one place but dispatch the preferences in the Services?”. There are two main differences between an API client implementation and a preferences access system:

- an API client has dynamic behaviors and is rarely stateless: authentication token, retry mechanisms… A good preferences system has none of these (or shouldn’t).

- an API client uses and exposes a backend model. It is (or should be) structured, and its list of endpoints can be an entry point in reading your business code. This backend model structure is a constraining input that deserves to be explicit. Preferences are just a persistence mean used in limited conditions.

So yeah, not the same at all.

6. Split your Model

You can read many advices about files and function lengths, and you should absolutely apply them to your Services. Your Model should evolve as the implementation clarifies the technical constraints. The business layer is the layer where you shouldn’t make compromises and let technical debt settle. As soon as a Service is too big or its responsibility seems a bit fuzzy, take a step back and draw a variation of your Model. It should often lead to splitting a Service, but sometimes you can also centralize in a new Service responsibility dispatched in multiple others.

Still remember: don’t atomize your Model!

7. Services naming

Name interfaces, not implementations. Don’t implement a Service named MyService and name its interface MyServiceItf. Because the default representation of your Service across the app should be its interface (and you should try to write it first!). If you don’t have any clever name for your implementation, then just use a suffix: MyServiceImpl.

There are many advices around the importance of naming worth reading. A great advice is to avoid generic suffixes like Manager. Indeed it can lead to classes like BookManager whose responsibility is to manage everything about books, and that’s clearly a bad scope definition. So we should find the right words to describe this class’s responsibility. BookOrderValidator, BookLendingMonitor…

But thinking about newcomers, flagging your interfaces with their nature as a suffix has value as it increases architecture’s readability. So here’s my unpopular opinion: enforce your classes (or interfaces) nature readability at least by using Service suffixes. The layers of the architecture and its shape will be quicker to grasp.

Also, if your Model is not well defined at some time (because specs are fuzzy, as it happens like always), allow yourself to temporarily have vague responsibility services. BookService is ok as long as you take care of splitting it to properly scoped Services as it grows. And if it doesn’t grow or evolve enough to be worth splitting, then no big deal. It’s readable and takes care of everything related to books: that’s a good enough name and Model!

8. Don’t dispatch your code

I’ll start with an example. My personal taste leads me to declare:

- a Service interface on top of its file

- the Service’s specific entities right after

- then the Service’s implementation

- and its mock at the bottom

Because the most important thing to expose when someone looks at your Service is its interface. Entities should not be far in order to get what’s used in its interface.

Of course if a file becomes too large and splitting the Service is not relevant then I extract the parts in the reversed order. Also I then try to keep their files together.

Systematically separating things by nature is a storage organization reflex that deteriorates readability and maintainability. It’s easier to forget about an entity becoming an orphan when you refactor a Service when it’s stored in a huge folder grouping all your business entities. That’s also the reason why UI is often organized in ducks: Views close to their ViewModels.

Group inside a file or group in the folders hierarchy: there are many possible practices and choices around this consideration, up to you to find yours.

9. Untested proposal: name Services that are exposed to UI differently

I know I wrote the opposite earlier (don’t split the Model into multiple layers). But identifying by name Services that UI devs are supposed to use or not may prove itself useful. Indeed, even if they don’t bypass the golden rule and use repositories directly, I already saw confusion between well defined Services. This happens because developers that focus mainly on the UI just don’t know the Model on their fingertips, and we shouldn’t expect them to do so.

I think this distinction could also bring some overall clarity.

I would suggest to name “UX Services” using the UXServicesuffix, simply keeping Service suffix for “Business Only Services”.

VIII. Conclusion

As you saw, above are pretty general considerations and no sample code. I still have doubts about the very wide ambition of this article. But in the end, everything I wanted to write down is. And I skipped many crucial topics that are directly related: Dependencies Injection, Testing (UTs, UI Tests, previews), Declarative UI practices… This would have been too much for sure.

I hope some of you will reach this conclusion and benefit from what I wrote.

And as always, I’m eager for your comments and critics, being them mean or off the point.

Do not hesitate!